News & Media

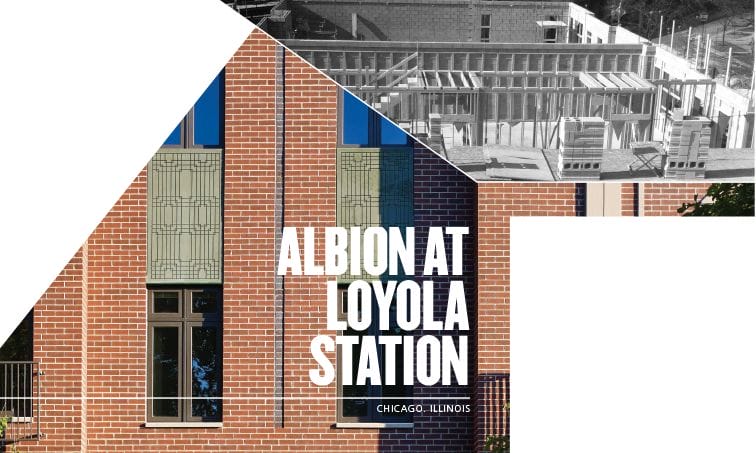

Keeping it in Full Swing: Albion at Loyola Station

Elevation 004

For Loyola University Chicago, creating a community reaches beyond the immediate campus. The faith-based institution has supported its Rogers Park neighborhood with the development of new luxury rental housing, retail spaces and a parking garage. The most recent endeavor is Albion at Loyola Station, a 29-unit, market rate apartment complex that opened last May.

“Loyola believes that campus and community are joined together, and we are investing capital dollars in our vision of a safe, secure neighborhood for everyone,” said Peter Schlecht, senior project manager at LUC.

The handsome three-story brick apartment buildings today anchor Albion Avenue near the CTA Red Line’s Loyola station. They reveal no hint of the myriad challenges this location presented: an irregularly-shaped site, elevated rail tracks and utility poles along boundary lines, and unsuitable soils.

The compact triangular lot had been used for decades for overflow parking. To maximize the space, the architect designed the 43,000-square-foot Albion at Loyola Station as five side-by-side buildings. They are configured with six units per building for a total of 28 two-bedroom apartments and one four-bedroom apartment plus a mechanical room. Parking spaces are tucked behind the buildings.

It’s a tight fit. The rear boundary is angled and abuts a one-story concrete retaining wall that supports CTA elevated train tracks. The apartment buildings are sandwiched between tracks on the west and ComEd utility poles on the east, with just a five-foot clearance on each side. Neither the tracks nor the poles could be moved. It was up to the project team to work around them.

ComEd and CTA were brought on board during the pre-construction phase. The project team wanted to share its plans and incorporate the other stakeholders’ concerns and recommendations. Doing so from the start would save backtracking later.

Safety, for example, was a serious issue for CTA. The tracks were very close to some apartment balconies. To help mitigate safety concerns, Skender erected plywood sheeting to shield the construction from the view—and reach—of train passengers and passersby. The contractor also lowered the hydraulic scaffolding at the end of each workday. Another CTA concern was how vibrations caused during excavation and construction might impact the tracks and retaining wall. The agency was able to review and approve the development program for reassurance.

Over on the east side, ComEd agreed to re-locate some of the switches on its utility poles and re-string power lines to provide greater clearance for the crews. Even so, the project team had to change the way they constructed the outer walls in that area. Traditionally, they would complete the inner block layer and then the outer brick layer while working outside the structure. Because they were cramped for space, they built both layers simultaneously, one row at a time, from inside the structure, using a method called overhand brick-laying. The architect also made a small design modification to a cornice to shorten it.

But before the construction could start, the site had to be excavated. That’s when crews discovered remnants and remains of buildings and businesses that once stood there. The buildings were long gone, but the foundations had been left in place and buried, a common practice at the time. They had to be removed. In addition, the chemical waste left behind by a former automotive garage had contaminated the soil, which required remediation to meet environmental standards.

These issues and more were resolved through proactive planning and involving subcontractors early and throughout the process. Lean Construction practices guided the process and accelerated the project schedule. When the unforeseen surprises emerged, overtime charges were avoided by engaging the entire project team —including subcontractors and suppliers —to make adjustments to the plan and re-sequence the project. The project was finished three weeks ahead of time at no additional cost. Crews worked only one Saturday, and that was because of inclement weather.

Schlecht, who had not previously worked with Lean, is more than pleased with how the process works and the outcome.

“It was a huge advantage,” he said. “They had the whole project planned out ahead of time as opposed to reacting to situations. The schedule was detailed and results-oriented, day by day and item by item. There was always a cause and effect. If we got pushed out of one thing, there were always other things we could do to get back on schedule.”